counting days

Duration

Artists

Naeem Mohaiemen

Curation

Project coordinator

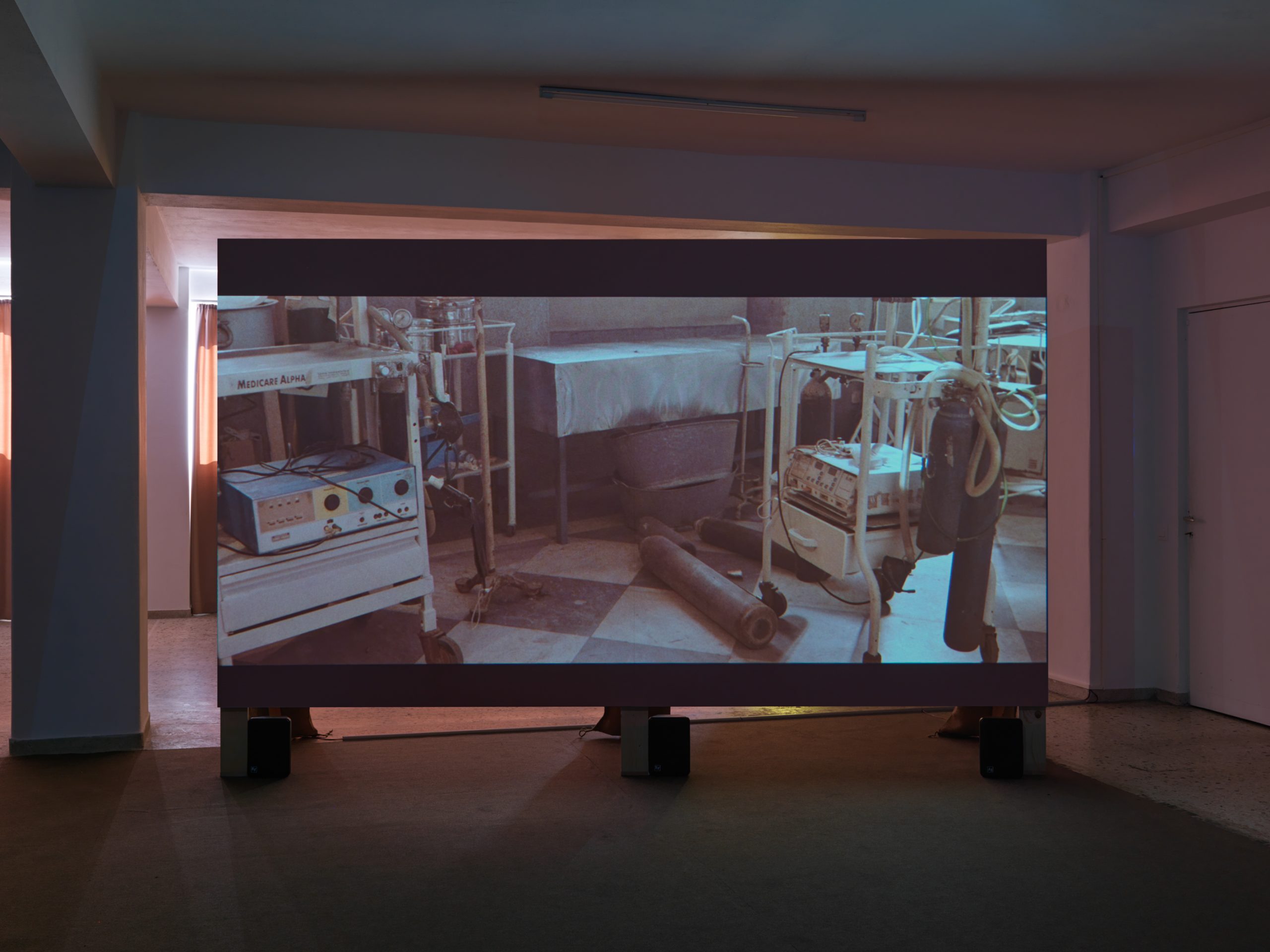

This text proposes a viewing of the exhibition Counting Days through the lens of intimacy and authority. The exhibition consists of two works put into dialogue for the first time: Jole Dobe Na (Those Who Do Not Drown), a film by the New York based artist Naeem Mohaiemen which explores an intimate story of loss and care, and Untold Intimacy of Digits (UID), a digital animation by the Delhi-based trio Raqs Media Collective which focuses on identification technologies. Jole Dobe Na was commissioned by the Yokohama Triennale, curated by Raqs Media Collective, and Bildmuseet in Sweden. In fact, UID served as a prompt for a scene in this film which was then presented under Raqs’ curatorial rubric of Afterglow, which questioned different approaches to care.

The fortified role of biotechnology in the pharma-medical and state apparatus of security and surveillance intimately linked with the body could add some interesting layers to the aforesaid works:

In 2016, India’s government established Aadhaar, a biometric database by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI). This database randomly generates a 12-digit number based on biometric data: ten fingerprints, two iris scans and one facial photo. This number is essential in order to access the state services of the Indian government and even private services like DHL. Here, we witness a succession of state controls ranging from the first analog identification technologies such as the 1858 handprint of Raj Konai depicted in UID, the popular model of fingerprint bases and today’s digitized biometric databases.

In 2020, due to the health crisis of COVID-19 that occurred before Mohaiemen’s film completion, policing was reinforced in many countries where citizens had to provide their exact geo-location and medical data. Note that I differ from right-wing conspiracy theories or Agamben’s delusional anti-vaccination statements in the name of freedom but I do believe we should be sceptical about the amount of biomedical information we provide generously both in everyday and exceptional situations.

Based on the aforementioned layers, I would like to focus on the resistance to authority upon the intimate. Intimacy could be defined in the following way: originating from the Latin word “intimus” meaning inmost, if we consider the “in” as inside. In the cases we examine, I can’t help but wonder if there is something more intimate than the body itself.

Moreover, I believe this definition of intimacy suggests a dialectical relationship; a binary movement “inside-outside” with multiple correlations that are affected both by desire and resistance.

Mohaiemen challenges the authority of the medical gaze upon the experience of patients by presenting the intimate relationship of Sufiya and Jyoti. Certain scenes worth special mention: Jyoti pushing the wheelchair of Sufiya in the courtyard as she playfully asks him to run faster or their serenade moment under an operating theater lamp. The intimacy presented here has a political dimension as the hierarchies imposed by mechanisms of pharma-medical institutions, as well as the consequent ideological constructions are destabilized. Nevertheless, the sovereignty of the pharma-medical apparatus is not completely dissolved. Some reminders appear during the film: The sign ‘OBSERVATION WARD’ appears above Sufiya’s head, flashes of images related to the pharma-medical apparatus disrupting the flow of the film i.e. microscopes, microbes etc. and Jyoti’s line: “The ruler says: All this is for your safety. New ways of separation. But we keep embracing our differences”. Another mechanism of necropolitics appears vaguely while Jyoti combs Sufiya’s hair, related to the tradition of memento mori. The couple is in an interfaith union, Muslim-Hindu, a coupling often not acceptable in India and Bangladesh so we can suppose that certain hierarchies come into play in the transition from hospital to an equivalent “cemetery”.

Intimate nursing and intimacy in life limiting conditions are rarely represented in the arts. Therefore, I take the opportunity to contextualize Mohaiemen’s work through the optics of care when related to loss. Jole Dobe Na provides a number of opportunities of resistance to the control over the narrative of lived experience against systematization of the medical gaze. Intimate nursing is seen as care by a nurse that entails physical proximity and often relates to touch. There is an ethos attached to intimate nursing based on trust, respect, empathy and ethical use of power because the relationship is by nature asymmetrical. Especially, in moments of care, touch becomes an urgent issue. Also, intimacy and sexuality are resurgent issues in palliative care with little visibility. Care experts provide opportunities to patients or/ and their partners to address their needs and desires within a limited-time window. During the pandemic the lack of touch was a central issue for everyone, not only for patients and high-risk groups. Indirectly the hesitant intimacy we experienced during the pandemic and the fear of dying alone become very present in the film while intimacy becomes an exercise of interdependence. This is why, for me, it makes most sense to speak about care and loss right now. We need to get more comfortable with these conversations as the consequences of climate change will be felt by a growing number of people even in places we consider as safe zones.

Raqs Media Collective are no stranger to the care field either. Here, they use the palm as a symbol for the biopolitical body. The animation is based on the handprint of Bengali peasant Raj Konai that was taken by force in 1858. The handprint originally acted as a form of written agreement. Today, it is found at the collection of the Francis Galton laboratory in University College London. This handprint was the beginning of the fingerprint system or ‘human control factory’ where the individual body becomes representable within a state apparatus. The subjugation is doubled if we think about the position of the colonial subject integrating the archive.

The animated palm seems to count again and again the fingers as people are rendered quantifiable. Here lies the paradox of identification technologies: the more information you provide about your individual identity, the more you are losing it and becoming anonymous, a number in the crowd, an isolated wave in the ocean of biopower, a sellable data. Still, there are opportunities for resistance to subjugation through the continuous gesture against the static-ness of the archive, the fortune-telling and spiritual element of the palm and the transformation of digits into language.

Inspired by the performance theorist Diana Taylor and her distinction between the archive (i.e., texts, documents, buildings, bones) and the so-called ephemeral repertoire of embodied practice/knowledge (i.e., spoken language, dance, sports, ritual)[1], the gesture of continuous counting testifies to the subjugated subjects’ resistance. Also, the print is reconfigured to produce an alphabet of gestures. Each sign corresponds to the letters of standard American Sign Language. The words “I” and “we” perfectly echo the tension of the individual and the collective. Last but not least, the corporeal element of the handprint, the palm that revokes the human essence and spirituality in Buddhism and elsewhere, the multiplicity of meaning of chiromancy constantly escaping the singular categorization and certainty that is found in the core of the archive as a state apparatus of power.

To summarize, the works presented in Counting Days provide a welcome platform to discuss burning pre-existent issues of the extended care field: intimate nursing, intimacy and sexuality in palliative care, afterlife care, control of medical data etc. that have resurfaced and have been generalized due to the current health crisis. Examining the works through the notion of the intimate, the most profound and singular element of human experience, defined by its proximity to the organic body as well as preverbal sensations[2], allows for a negotiation and temporary destabilization of authority, pharma-medical, state or other. The title though remains enigmatic – we do not know if we should count forward or backward – preparing us for the shape of a future that has not yet been[3].

Eleni Riga

[1] Taylor D., The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas, Duke University Press Books (September 12, 2003), p.19

[2] Kristeva J., The Sense and Non-Sense of Revolt, Columbia University Press (December 15, 2001), p.44

[3] Lorde A., Dream of Europe, Kenning Editions (Spring 2020), p. 117, http://deappel.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/DreamDeAppelReads-excerpt.pdf, last accessed on October 19, 2021.

~

Raqs Media Collective (* 1992 by Jeebesh Bagchi, Monica Narula, Shuddhabrata Sengupta). The word “raqs” in several languages denotes an intensification of awareness and presence attained by whirling, turning, being in a state of revolution. Raqs take this sense to mean ‘kinetic contemplation’ and a restless and energetic entanglement with the world, and with time. Raqs enlists objects such as an early-modern tiger-automata from Southern India, or a biscuit from the Paris Commune, or a cup salvaged from an ancient Mediterranean shipwreck to sniff and taste time. Such and other devices are played with in order to undertake historical subterfuge and fabulist adventures. Raqs practices across several media; making installation, sculpture, video, performance, text, lexica, and curation. Their work finds them at the intersection of contemporary art, philosophical speculation and historical enquiry. They were the artistic directors of the Yokohama Triennale 2020, “Afterglow”. Ongoing exhibitions include “The Laughter of Tears” at the Kunstverein Braunschweig (2021), and “Hungry for Time”, an invitation to epistemic disobedience with the collections of the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna (2021).

Naeem Mohaiemen combines films, photography, drawings, and essays to research the many forms of utopia-dystopia (families, borders, architecture, and uprisings)– beginning from South Asia’s two postcolonial markers (1947, 1971) and then radiating outward to unlikely transnational alliances and collisions. His fiction film Tripoli Cancelled, filmed at Ellinikon Airport in 2016 and starring Greek-Iranian actor Vassilis Koukalani, premiered at Documenta 14, Athens. He co-organized with the EMST education department What We Found After You Left, a project at Ellinikon by Greek photography students of FOCUS and 26 ANO which premiered at EMST and then traveled to Power Plant (Canada) and Terminal (New Zealand). He also presented “Mohammad Ali’s Bangladesh Passport” and “Century’s Container” at Athens Municipality Arts Center at Parko Eleftherias, “Volume Eleven: Flaw in the Algorithm of Cosmopolitanism” at National Library of Athens, and “Afsan’s Long Day” in the group show “The Thickness of Time” curated by Locus Athens at Akadimias 23.